Hackers Could Tap Into Smart Light Bulbs, Research Shows

SAN FRANCISCO—The so-called Internet of Things, its proponents argue, offers many benefits: energy efficiency, technology so convenient it can anticipate what you want, even reduced congestion on the roads.

Now here’s the bad news: Putting in one area could prove irresistible to hackers. And it could allow them to spread malicious code through the air, like a flu virus on an airplane.

Researchers report in a paper to be made public on Thursday that they have uncovered a flaw in a wireless technology that is often included in smart home devices like lights, switches, locks, thermostats and many of the components of the much-ballyhooed “smart home” of the future.

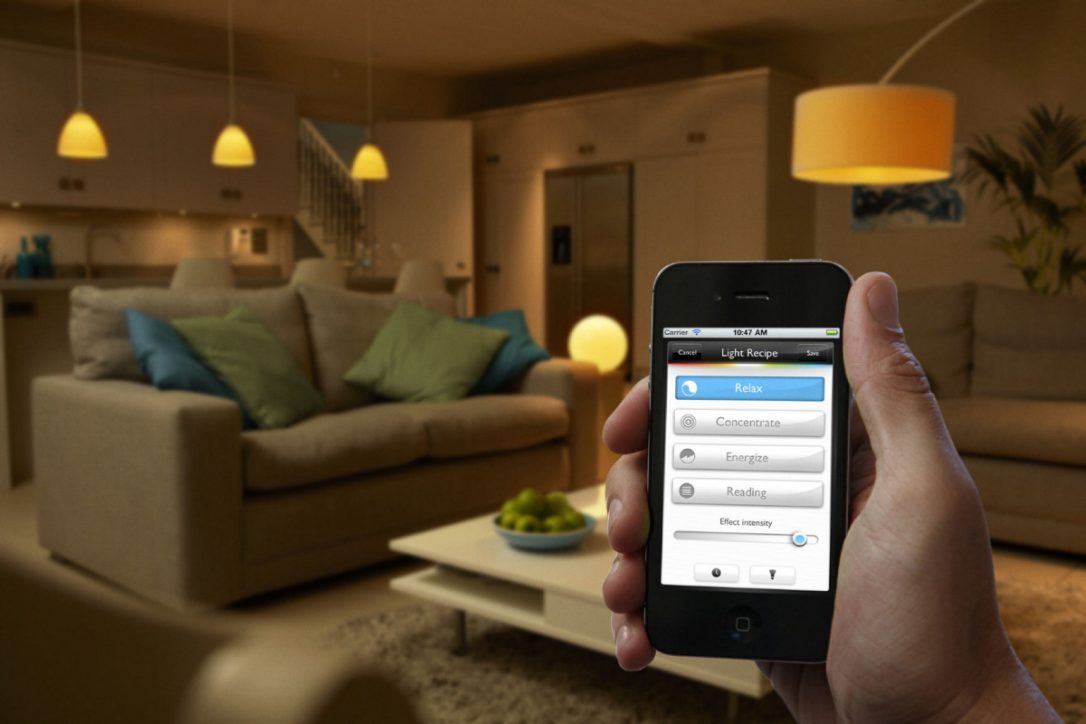

The researchers focused on the Philips Hue smart light bulb and found that the wireless flaw could allow hackers to take control of the light bulbs, according to researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science near Tel Aviv and Dalhousie University in Halifax, Canada.

That may not sound like a big deal. But imagine thousands or even hundreds of thousands of Internet-connected devices in proximity. Malware created by hackers could be spread like a pathogen among the devices by compromising just one of them.

And they wouldn’t have to have direct access to the devices to infect them: The researchers were able to spread infection in a network inside a building by driving a car 229 feet away.

Just two weeks ago, hackers briefly denied access to whole chunks of the Internet by creating a flood of traffic that overwhelmed the servers of a New Hampshire company called Dyn, which helps manage key components of the Internet.

Security experts say they believe the hackers found the horsepower necessary for their attack by taking control of a range of Internet-connected devices, but the hackers did not use the method detailed in the report being made public Thursday. One Chinese wireless camera manufacturer said weak passwords on some of its products were partly to blame for the attack.

Though it was not the first time hackers used the Internet of Things to power an attack, the scale of the effort against Dyn was a revelation to people who didn’t realize that having internet-connected things knitted into daily life would come with new risks.

“Even the best internet defence technologies would not stop such an attack,” said Adi Shamir, a widely respected cryptographer who helped pioneer modern encryption methods and is one of the authors of the report.

The new risk comes from a little-known radio protocol called ZigBee. Created in the 1990s, ZigBee is a wireless standard widely used in home consumer devices. While it is supposed to be secure, it hasn’t been held up to the scrutiny of other security methods used around the Internet.

The researchers found that the ZigBee standard can be used to create a so-called computer worm to spread malicious software among internet-connected devices.

Computer worms, which can keep replicating from one device to another, get less attention these days, but in the early years of the commercial Internet, they were a menace. In 1988, one worm by some estimates brought down a tenth of the computers connected to the Internet.

Since then, the number of Internet-connected devices has spiralled into the billions, and with it the risks of a cleverly created worm.

So what could hackers do with the compromised devices? For one, they could create programs that help in attacks like the one that hit Dyn. Or they could be a springboard to steal information, or just send spam.

They could also set an LED light into a strobe pattern that could trigger epileptic seizures or just make people very uncomfortable. It may sound far-fetched, but that possibility has already been proved by the researchers.

The colour and brightness of the Philips Hue smart light bulb can be controlled from a computer or a smartphone. The researchers showed that by compromising a single light bulb, it was possible to infect a large number of nearby lights within minutes. The worm program carried a malicious payload to each light — even if they were not part of the same private network.

In creating a model of the infection process, they simulated the distribution of the lights in Paris over an area of about 40 square miles and noted that the attack would potentially spread when as few as 15,000 devices were in place over that area.

The researcher said they had notified Philips of the potential vulnerability and the company had asked the researchers not to go public with the research paper until it had been corrected. Philips fixed the vulnerability in a patch issued on Oct. 4 and recommended that customers install it through a smartphone application. Still, it played down the significance of the problem.

“We have assessed the security impact as low given that specialist hardware, unpublished software and proximity to Philips Hue lights are required to perform a theoretical attack,” Beth Brenner, a Philips spokesperson, said in an emailed statement.

To perfect their attack, the researchers said they needed to overcome two separate technical challenges. They first found a “major bug” in the way the wireless communications system for the lights had been executed, which made it possible to “yank” already installed lamps from their existing networks.

The researchers then used what cryptographers describe as a “side channel” attack to purloin the key that Philips uses to authenticate new software. The term side channel refers to the clever use of information about how a particular encryption scheme is used.

“We used only readily available equipment costing a few hundred dollars, and managed to find this key without seeing any actual updates,” the researchers wrote. “This demonstrates once again how difficult it is to get security right even for a large company that uses standard cryptographic techniques to protect a major product.”