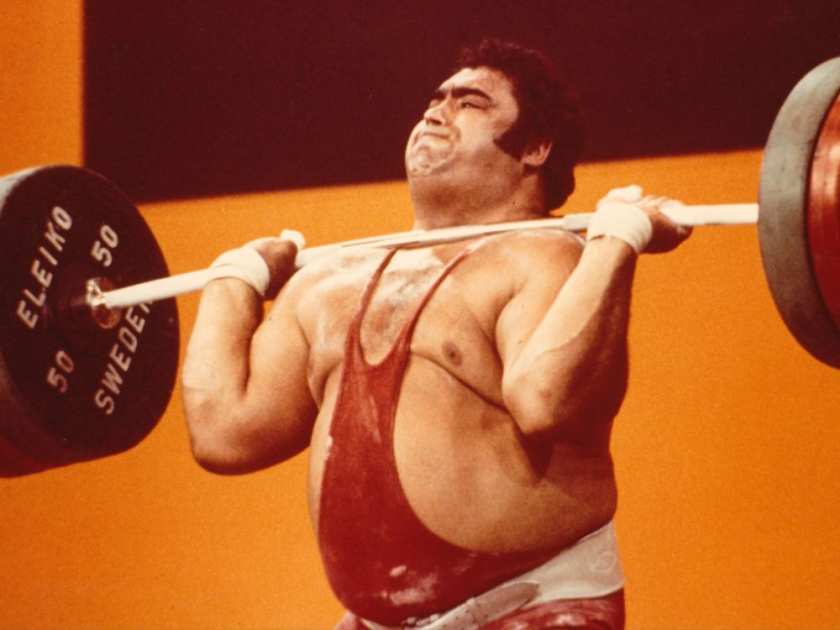

Montreal Olympics: Soviet Weightlifter Vasily Alekseyev Was a Real-life Hercules

There were 6,084 athletes who took part in the 1976 Olympic Games, but there was one who was definitely larger than life: Vasily Alexeev.

The weightlifter from the Soviet Union stood 6-foot-1 and weighed 345 pounds. In a Sports Illustrated cover story feature that was published a year before the Montreal Games under the headline World’s Strongest Man, writer William O. Johnson described Alexeev (since transliterated as Alekseyev) as “the premier sports hero of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.”

In a Russian documentary titled Vasily Alekseyev, The Triumph of Strength, actor Aleksey Petrenko recalls that the weightlifter once wrote: “Every time I see myself in the mirror I almost feel like asking myself for an autograph.”

It would have taken a very big mirror to fit this real-life Hercules.

Alekseyev came to Montreal as the defending Olympic champion after winning gold at the 1972 Munich Games. He was unbeaten since 1970, the same year he broke the 600-kilogram mark (1,322 pounds) for combined lifts in three disciplines: the snatch, clean and jerk and clean and press. Alekseyev would later set a world record of 645 kg.

On the morning of his gold-medal performance in Munich — in which he lifted 640 kg — Alekseyev was reported to have eaten 26 fried eggs and a steak for breakfast. With a diet like that, it shouldn’t have come as a surprise when he died of a heart attack in 2011 at age 69 after being admitted to a clinic in Germany.

Coming into the 1976 Olympics, the 34-year-old Alekseyev was suspected of steroid use after showing up late for a routine pre-competition physical in Montreal, but would later pass his test before the Games began. The 1976 Olympics were the first Games that would have steroid testing.

“I was lifting those weights without any drugs,” Alekseyev insisted in the documentary.

You could hear a pin drop at the St. Michel Arena on July 27, 1976, when Alekseyev prepared to lift what would be a world-record 255 kg (562 pounds) over his head in the clean and jerk. There was a roar when he lifted the bar up to his shoulders and the Soviet coaches motioned for the crowd to be quiet. Five seconds later, Alekseyev hoisted the weight above his head as his legs started to shake and he stumbled a couple of small steps backwards. He managed to stabilize himself and the judge gave him the signal to drop the barbell. He did and the whole arena seemed to shake.

Alekseyev was a gold medallist again after already setting an Olympic record with a lift of 185 kg (408 pounds) in the snatch. Alekseyev’s combined total of 440 kg for the two lifts (the clean and press was dropped after the ’72 Games) was 35 kg (77 pounds) more than East German Gerd Bonk, who won silver, and 52.5 kg (115 pounds) more than bronze medallist Helmut Losch, also from East Germany. Alekseyev’s Olympic-record total of 440 kg stood until the 1988 Games in Seoul, South Korea, when the Soviet Union’s Aleksandr Kurlovich lifted 462.5 kg.

Alekseyev wasn’t only a man of super strength. He had many interests and his favourite hobby was reading. He also liked to garden, cook, sing and was a talented carpenter. He enjoyed playing billiards, table tennis and even volleyball. He spoke some English, French and German. His official job in the Soviet Union was as a mining engineer.

He didn’t have much time for TV.

“There is too much literature, too much music in life to spend time at television,” he told Johnson in his 1975 Sports Illustrated feature.

Alekseyev also didn’t have much use for coaches.

“Should I listen to the coaches who are worse than me in that sport?” he asked in the documentary. “Of course, I didn’t listen to anyone. I did everything on my own.”

That didn’t always sit well with Soviet Union sports officials as Alekseyev trained by himself with all sorts of self-made apparatus and twice-a-day lifting sessions.

“The difference between my methods and others is great,” Alekseyev told Sports Illustrated’s Johnson. “What is mainly different is that I train more often and I lift more weights than others. I never know when I will train. Sometimes deep in the night, sometimes in the morning. Sometimes several times a day, sometimes not at all. I never repeat myself. Only I understand what is right for me. I have never had a coach. I know my own possibilities best. No coach knows them. Coaches grow old and they have old ideas.”

Alekseyev grew up in Shakhty, a coal-mining city, but his father was a lumberjack. At age 11, he started developing his strength by pushing logs into the water and his first weightlifting barbell was an axle from an old truck.

In the documentary, Alekseyev talks about his fear as a boy of shaking a girl’s hand or pulling on a door handle, worried he might break them. He would eventually meet Olympiada Ivanovna and they would have two sons together, Sergey and Dmitry.

During the documentary, in which Alekseyev and Ivanovna are shown celebrating their 48th wedding anniversary, the weightlifter is asked about his gold-medal performance in Montreal.

“Back then I performed really well,” he said. “It was the first time there were tests for steroids. Everyone had performed badly apart from me.

“When all the journalists filled the podium they asked me: ‘How did everyone perform so poorly and you, Mr. Alekseyev, set a fantastic world record?’ So I said: ‘It depends on what you live on.’ They thought that I, just like everyone else, was taking steroids. My victory was the only proof.”

Alekseyev’s unbeaten streak, which started in 1970, ended at the 1978 world championships, where he suffered a hip injury.

Two years later, Alekseyev took centre stage at the Moscow Olympics in front of his own people. It didn’t go well.

Alekseyev was eliminated when he failed on all three attempts at 180 kg (397 pounds) in the snatch — five kg less than he had lifted in Montreal. The Soviet fans quickly turned on their “premier sports hero,” jeering and whistling. It marked the end of Alekseyev’s competitive career after winning two Olympic gold medals, eight world championships and setting 80 world records.

After years of parading Alekseyev around as a sign of Soviet Union strength, the motherland started to treat him like a “stepchild” after the Moscow Games, according to the documentary. Alekseyev insisted someone had poisoned him with a drink he had been given shortly before attempting his lifts that made him feel “weak.”

In Johnson’s Sports Illustrated feature, Alekseyev told him: “Do not forget one thing.” He then paused. “I am original.” He paused again. “I am unique.”